Interstate 17, Anthem, Arizona

October 9, 2009

6:17 PM

“Your Dad just passed.”

“Oh, Mom… I’m so sorry. I’m on my way there now. I thought… I thought he had more time. I thought…”

“I felt his last breath. I held his hand. I…” She couldn’t talk anymore.

“I’ll call people. You try to get some rest. Who’s there with you now?”

“Marie Beth got here right after it happened.”

“She’ll take good care of you. I’ll be there in a couple of hours.”

“Sheldon and Jan know. They’re coming. Sheldon was at a football game.”

“It’s okay, Mom. We still have each other. We still have family. We’ll get through this together. It’s what we do.”

There was silence, and just a brief sob on the other end of the phone.

“You lie down Mom. Embee will take care of you. We’re all coming, Mom. You’re not alone. Okay?”

The phone clicked. The roaring of the road was cold. Horace’s vision blurred a bit, and he took a deep breath. “I have to be strong now. Mom will be coming apart when I get there. I have to help her through this.” He gave instructions to his phone to call his best friend. He would make calls for most of the trip between Anthem and Flagstaff, spreading the news of his father’s demise across the country.

Henderson, Nebraska

January 12, 1964

6:23 PM

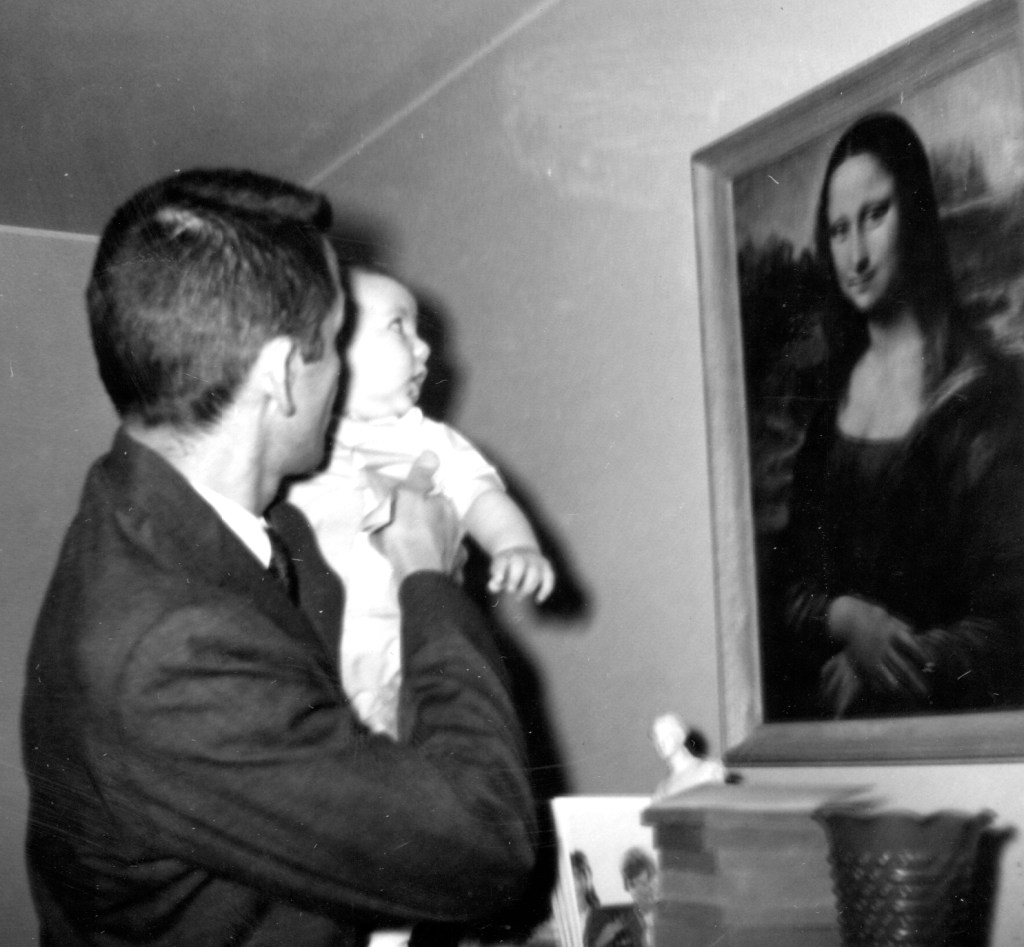

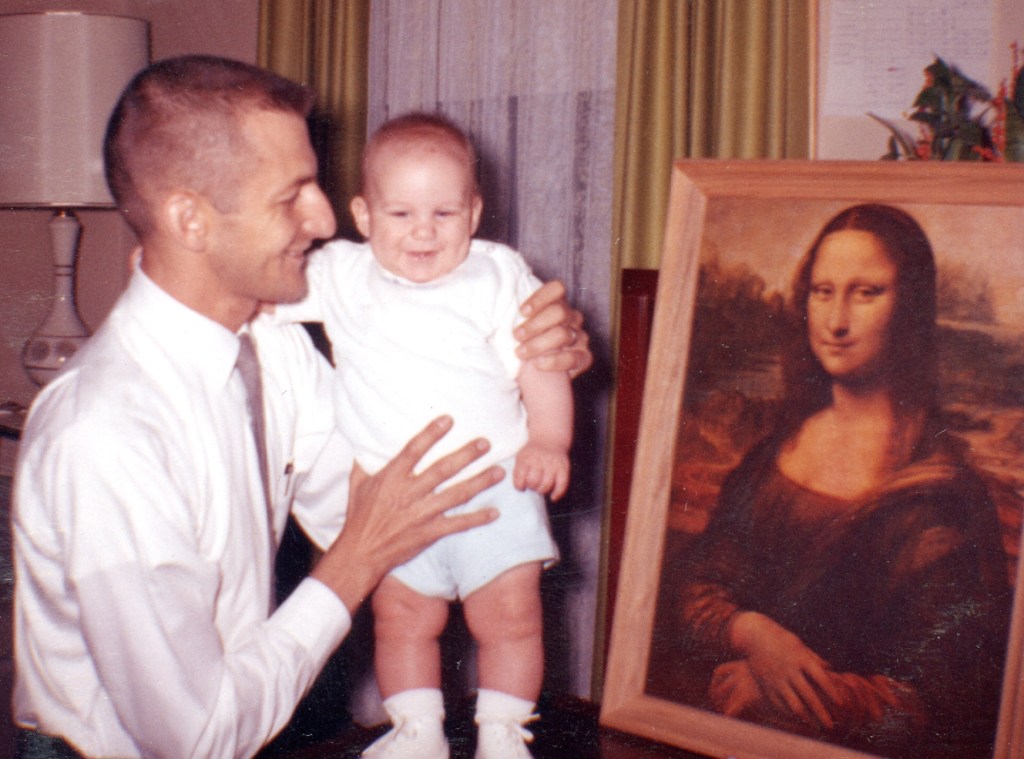

“Lay dee,” said the infant Horace.

Hal was holding Horace lovingly in his thin arms. “You want to go see The Lady?” He walked past Marie, and into the living room.

“If he wants to see his Mom,” said Owen Leal, Horace’s grandfather, “you just walked right past her.”

“No,” said Marie. “I’m Mama. Lady is The Mona Lisa.”

Hal stood next to the painting, and Horace began to wave. “She’s a nice lady, isn’t she?”

Horace giggled, and he put his index finger on her lips.

“She has a pretty smile, doesn’t she?” Marie asked.

Horace began to dance in his father’s arms, bouncing up and down.

“I’ll get it,” said Marie, and she went to the record player, and dropped the needle on “On The Trail” from “The Grand Canyon Suite” by Ferde Grofe. She picked up the camera next to the turntable, and she returned to her husband and son.

Horace grinned, jumped up and down some more, and pointed at the painting. “Lay Dee!”

Marie took the picture.

“You’re making an art lover of that boy,” said Owen. “Good for you, Hal.”

Horace began to wave his hands back and forth, and he tilted his head back.

“Oh, no!” whispered Owen. “Are the demons returning?”

“No, Dad, not this time.” Marie shot Hal a glance that told him to let it go. “He’s conducting. He’s seen his brother, Sheldon, doing that when we play Beethoven. Sheldon has decided he will be the next Leonard Bernstein.”

“Is he still having as many possessions?”

Hal was grinning at Horace. “Yeah, Pastor Leal, he’s still having seizures. We’re going to another specialist next month after I get paid.”

“You know you’re wasting your money. I could do an exorcism. We don’t even need to go to the church. I could do it here for you at no—”

“Thank you, Pastor, but I believe we’re going to go with the doctors.”

“You’re not rich folks. You don’t make enough teaching those high school classes to be wastin’ money on what doesn’t work. You’ve been to seven doctors already, and they haven’t fixed it. God doesn’t need money. All he needs is your faith and someone who is ready to remove the demons from little Horace’s soul.”

“He had one this morning right after he drank some orange juice. I wonder if that’s connected somehow.” Marie’s face was troubled.

“He’s also had seizures when waking up from his naps, when eating Gerber baby food, after bowel movements, and before them. Any of those could be causes, but they don’t all line up. So far, just about the only thing that doesn’t seem to set them off is the Mona Lisa and Music.

Interstate 17

October 9, 2009

6:59 PM

Nat King Cole was singing on the radio as Horace hung up the last phone call.

Many dreams have been brought to your doorstep

They just lie there and they die there

Are you warm, are you real, Mona Lisa?

Or just a cold and lonely lovely work of art?

He had told his best friend, who cried, although Horace had maintained his composure. He was all but clinical when he told her. He was surprised by Monica’s reaction. She’d only met Hal twice. Why would this news hit her so hard? Horace reminded himself, once again, he didn’t understand people.

He was gaining strength with every mile. He was remembering how, less than a week ago, his sister had screamed at his mother because Marie had neglected to keep Jan up to date on Hal’s condition. He could see vividly in his mind Marie falling apart. Her knees had buckled, and Horace had caught her and helped her to the couch. When Horace asked her to knock it off, Jan turned on Horace with even more ferocity. He had finally called his brother, Sheldon, to calm Jan down.

Marie was going to need all his help now. She would require all his strength. He was going to be there for her. He was going to be her comfort and her fortitude. That’s what he kept repeating to himself. Comfort and Fortitude. Just get Mom through this night.

It wasn’t as though no one had seen it coming.

Anthem Elementary School

September 20, 2009

9:23 AM

“All right,” said Horace to the eager faced fifth graders. “What do we know?”

“We know the bed was bolted to the floor,” shouted Yoli, a girl not prone to raising her hand.

“Okay, good. Now, what does that mean about the bed?”

“It means Julia couldn’t move it, no matter what.” This was Armando, a kid two sizes too big to be in fifth grade.

“Hmm,” mused Horace. “I wonder why Roylott wouldn’t want her to move the bed. Is there anything around the bed that could be relevant?”

There was silence while the faces of 28 kids contorted in thought. Horace ambled over toward the vent, and inconspicuously put his hand on it.

“The vent! The vent! It’s over the bed!” These were random shouts scattered through the room.

“So, Amanda, what would be so important about the bed being near the vent?”

“Maybe…” and Amanda put her hand on her chin, as she had seen her teacher do so many times. “Maybe it was poison gas that he pumped through the vent?”

“How would he keep the gas from killing him? His room is on the other side of the vent.”

Again there was silence. After a moment, Jake, a boy two size too small to be a fifth grader, suggested, “Maybe that’s what that metallic clanging was? It was some kind of special machine that he puts against the vent, and it pushes gas into the room without letting it go through to his side of the room.”

“I like the way you think. That’s certainly possible. What do we know about the inside of Dr. Roylott’s room?”

“There’s a safe in there,” said Amanda.

“Yes, there is. It’s sitting on a table. Is there anything on the safe?”

Pages began flipping at desks throughout the room. “A saucer of milk.” This was the first time Christina had spoken in two days.

Horace smiled broadly. “Way to go, Christina!”

“So, he drinks milk,” said Armando sarcastically. “Big deal.”

“Do you drink your milk from a saucer?” Horace asked him, while shooting him a glare that made it clear we don’t step on Christina when she finally says something.

“I’ve never been kidnapped by aliens.”

The class laughed.

“A saucer is a really shallow bowl. You can’t, for example, have your cereal in one. And the only way to drink out of it is—”

“Licking it!” shouted Yoli. “Like a cat.”

“Do you suppose he keeps his cat in that safe?”

“That would be weird,” Yoli replied.

“Roylott killed his daughter. We already know he’s weird.” Amanda looked up at Horace. “Still, what’s the point of keeping a cat in a safe? Why not just let it wander around like everyone else does?”

“Good question. Was there anything else on the safe?”

“What’s a lash?” asked Christina.

“It’s the way Doyle spelled leash. You know, like you use for a dog? But there was something weird about the leash. Do you remember what was weird about it?”

“It’s tied in a weird little loop.”

“Nice, Antonio. It is. Why would you tie a leash like that do you think?”

“For something with a really small neck,” called out David, who came to class stoned at least twice a week.

“Sounds less like a cat all the time. What else could it be?”

Horace was thinking three questions ahead to the bell pull that rang nothing but ran from the vent to the pillow on the bed when his cell phone rang. Horace was startled, and he pulled it out of his pocket, annoyed. Everyone knew they should never call him during school. He looked at the name. “Mom.” “Shit,” he whispered. He pressed the button. “What’s the matter Mom?”

The class was stunned into silence. They’d never once seen their teacher answer his phone before. Their eyes widened as Horace’s face lost all of its color as though it were water slipping through a crack in the pipes.

“Oh my God…” Horace’s eyes teared up.

Amanda was out of her seat and running for the door before Horace got the next sentence out.

“Okay, Mom. I’m coming. I’ll be right there. I have to… you know… I have to… I have to get to the car. I’m coming Mom.” The classroom ceased to exist for Horace. His car, the interstate, Flagstaff, and the hospital were all he could see.

In another moment, Emily Johnson, one of the other teachers on his team, burst through the door. “I’ve got ‘em. You go. Just go.”

Horace looked up, tears streaming from his eyes. “Thank you. I… yeah. Um… Yeah. I gotta go. I’ll tell the office.”

When he reached the office the secretary ran to him, hugged him, and said, “Emily’s got it. Go. And we’re all praying for you and your Dad.”

Horace shot through the door and ran to his car.

Interstate 17

October 9, 2009

7:21 PM

So you got everything, ah, but nothing’s cool

They just found your father in the swimming pool

And you guess you won’t be going back to school

Anymore.

Billy Joel was singing as Horace pressed harder on the accelerator. He needed to be in Flagstaff. He shouldn’t have left. Going back to work was stupid. He should have known this was coming sooner than anyone hoped. In the only time the whole family had agreed on anything in more than three decades, they had voted as one to send Dad home to hospice when the doctors said there was no more they could do. Dad should die in his own bed, surrounded by those who loved him. They all believed that. It was moral. It was just. It was what Dad would want. When Science has reached its limits, only Love remains.

Hesperia, California

October 11, 1993

4:20 PM

“I don’t think she gets it. I mean, I try to explain an idea to her, and then she either hates it, and she gets pissed at me, or she goes apeshit and runs so deep with the idea that she twists it into something new and that it was never intended to be.” Horace glanced at the clock, cradled the phone between his neck and left shoulder, picked up the bong and took a hit while his Dad talked to him.

“And would it have been worth it, after all,” Dad recited,

After the cups, the marmalade, the tea,

Among the porcelain, among some talk of you and me,

Would it have been worth while,

To have bitten off the matter with a smile,

To have squeezed the universe into a ball

To roll it towards some overwhelming question,

To say: “I am Lazarus, come from the dead,

Come back to tell you all, I shall tell you all”—

If one, settling a pillow by her head

Should say: “That is not what I meant at all;

That is not it, at all.”

Horace exhaled as quietly as he could. “Yes! That’s it. That’s precisely it. Who is that?”

“I thought you had a degree in English. How did you get through four years of school without encountering TS Eliot?”

“We were dealing with Practical Cats.”

“You needed to deal with Prufrock.”

“So does Melinda. I’ll show her. She likes I’ll Fly Away. I have to give her credit for that.”

“She’s your wife. I hope there is much more than that you give her credit for.”

“For which I give her credit?”

“You know what Churchill said about ending sentences in prepositions.”

“No idea.”

“An intern was going over one of his speeches, and he told Churchill that he should rewrite a sentence because he ended it with a preposition. Churchill, quite properly, fired him at once saying, ‘that is the sort of nonsense up with which I will not put.’ A wise man, this Churchill.”

Horace laughed. “I want to preserve the language the way a chef preserves his knives. Every time we make it less precise, it becomes duller. It can’t communicate as clearly.”

“You’ve heard of evolution, haven’t you? All things change.”

“But not always for the better.”

“Well, maybe Shakespeare was actually talking about the language when he had Gertrude tell us all that lives must die, passing through nature…”

Interstate 17

October 9, 2009

7:43 PM

“… to eternity,” mumbled Horace. The road was dark, and there were few lights in the distance. He felt alone. The world had never been quite so empty. He’d made this drive dozens of times, but tonight he was travelling through an unfamiliar abyss. Mom had never needed him the way she will tonight. His job was to remain calm. He needed to hold Mom up. He needed to give her his strong heart to keep her from coming apart completely. That meant he was going to need some more strength of his own. Someone had to put some duct tape on the torn pieces of his heart. He thought of his cousin, and he picked up his phone.

Flagstaff, Arizona

August 30, 1985

5:46 PM

“… and with one phone call, his future begins,” said Hal, setting his beer on the kitchen table.

His wife, Marie, smiled at her son, Horace, as he spoke into the phone.

“Mrs. Burke? My name is Horace Singleman. I’ll be your student teacher this year. I’m calling to introduce myself and to find out if there’s anything special I should do, or bring, or… um… you know… think about for my first day.”

“Eloquent as ever,” whispered Marie.

“He’s nervous,” Hal whispered back. “Give the boy a break.”

“Yes, ma’am.” Horace was getting control of himself. “I’ll be sure to bring a lesson plan book, too. Is there a particular type you recommend?”

Hal laughed. “She’s not going to let him get by with that, is she Marie?”

Marie shook her head. “He’s not close to ready to do his lesson plans in those little blocks. He’ll need to…”

“Oh, yes, ma’am. I understand. So probably a wire notebook or…”

“Where should we take him for dinner? Do you think La Fonda is enough or…”

“No.” Hal shook his head. “This is the day his life changes. Let’s get the boy a steak.” Hal and Marie had never been so proud. Horace had never been more nervous.

Interstate 17

October 9, 2009

7:43 PM

Nervous. That was the best explanation. He was afraid he would fail his mother. “But screw thy courage to the sticking place, and we’ll not fail.” Maybe Lady Macbeth wasn’t the right person from whom to get emotional advice. She was a murderous bitch. On the other hand, Shakespeare often put his best advice in the mouths of his villains. And I’m responsible for who I am. Testing his memory, and finding his strength, Horace recited into the darkness:

No, no, no, no! Come, let’s away to prison:

We two alone will sing like birds i’ the cage:

When thou dost ask me blessing, I’ll kneel down,

And ask of thee forgiveness: so we’ll live,

And pray, and sing, and tell old tales, and laugh

At gilded butterflies, and hear poor rogues

Talk of court news; and we’ll talk with them too,

Who loses and who wins; who’s in, who’s out;

And take upon’s the mystery of things,

As if we were God’s spies: and we’ll wear out,

In a wall’d prison, packs and sects of great ones,

That ebb and flow by the moon.

Horace had printed that in appropriate script, and he had gotten it professionally framed for his Father. It had been on the wall in Dad’s office for decades. He knew Dad understood that they were God’s spies. No one else ever asked why that was on the wall. They just accepted that it was part of Horace and Dad.

And Horace had gotten through the whole thing, aloud, without crying. He was getting stronger. He would be all right. He could help his Mom.

Flagstaff, Arizona

October 3, 2009

8:18 AM

Horace gazed at his Father. Hal was in and out of consciousness, and he was clearly restless. He didn’t understand where he was. He didn’t know what was happening.

Marie set her hand gently on Horace’s shoulder. “Why don’t you read him some poetry? That soothes him.”

“Do you think he’ll understand?”

“Do you think it matters?” His nephew, Sheldon’s son, Leonard, sat on the other side of the table, and he gave Horace an annoyed glare.

“Good point.”

And Horace read. Hal didn’t seem aware of his surroundings, and yet, every few minutes, he would finish a line.

“And I am two-and-twenty,

And oh, ’tis true, ’tis true,” mumbled Hal as Horace read AE Houseman.

Horace smiled at his father. The things one remembers when one’s time is coming to a close. Hal recited lines about a patient etherized upon a table, and then, with the slowest, most graceful movement, turned his head and looked at his son. “Let us go and make our visit.” He almost smiled, but his lips wouldn’t quite go that far before Hal was asleep again.

Flagstaff, Arizona

October 9, 2009

8:12 PM

Horace pulled into his parents’ driveway. This wasn’t the house in which he had grown up. They’d sold that and moved into this much more easily maintained home in the Country Club. They had been here for five years now, and every time Horace arrived he felt as though he were visiting a foreign country. Tonight, it felt like an alien planet. How could it be that he would go through that door without his father greeting him?

“Strength, Horace. Your Mother needs your strength tonight. Hold it together. You’ve got this. You’re going to be just fine.”

The room wasn’t dark, but it certainly wasn’t glowing with the light he was accustomed to finding when he walked in. His eyes needed no time to adjust.

Mom was sitting at the kitchen table. Sheldon, Horace’s brother, was standing next to her, his hand on her shoulder.

Hal was lying on what appeared to be almost a stretcher. His eyes were closed. The light was dim, and Horace kept waiting to see him take just one breath. Horace took a deep one of his own, and went to his Mother to hug her. She needed his strength; he would….

On the wall to the right of his mother was a cheap calendar with the Mona Lisa on the front. And Horace lost all control of himself. He crumpled like bad prose on cheap paper to his knees and began bawling uncontrollably. His mother held him, but he couldn’t stop.

“He’s going to hyperventilate,” said Marie.

Sheldon got him a paper bag into which he told Horace to breathe. Horace didn’t want to breathe.

Flagstaff Funeral Home

October 21, 2009

3:47 PM

Horace looked out at the people. There must have been a hundred of them. It was standing room only. And they were looking at him. He hated that.

He didn’t want to speak here today. He and his brother had fought over the music Horace chose for their Father’s Memorial Video. Horace just wanted to hide where no one would ever find him again, but… here he was.

He had been talking for about ten minutes now. He had worked for days on what he would say, and he found himself resentful that his father wasn’t here to help him fix his prose. It was important. Dad had never let him down before, but now, when it mattered… he was nowhere to be found. He wished these people would stop looking at him. He looked down to his pages again. He knew better. He knew public speaking. He’d been a teacher for more than 20 years. He just couldn’t look at these people, and he buried himself in the safety of the printed word. He read aloud.

“And so now you’re gone, and while some see no tragedy in your passing, I see little else. I am grateful for the love I have for and get from all these people you gave me, but none of them, nor all of them combined, can ever give me what you did. I have no one to check my work. I have no one to explain to me what John Dewey meant about experience and education. I have no one to ask me what movies he should bother watching. I have no one with whom to argue about whether Fried Green Tomatoes belongs on the 100 Great Movies List. And I have no one to tell me that sentence would have seemed less awkward if I ended it with a preposition. And it just sucks.

“So, I know we have no Heaven for you. I know that you simply are no more. But, much as it would annoy you, I need to steal some other writers’ words now because they’re better than mine. Yes, I know which of the people listening to this are thinking, “That’s not saying much,” and I would like to direct to those people the napkin I would normally being throwing at you, Dad, for such an insolent thought. So, forgive me please, but remember that, “Good writers borrow from other writers; great writers steal from the outright.”

“So, “Let us go, then, you and I…”

–TS Eliot, from “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock

“When I think of your absence, I am forced, reluctantly, to admit that my mind goes somewhere you would loathe it for going. “He’s really not dead. As long as we remember him.”

“You don’t really need Heaven, though, anyway.

I have sometimes dreamt, at least, that when the Day of Judgment dawns and the great conquerors and lawyers and statesmen come to receive their rewards–their crowns, their laurels, their names carved indelibly upon imperishable marble–the Almighty will turn to Peter and will say, not without a certain envy when He sees us coming with our books under our arms, “Look, these need no reward. We have nothing to give them here. They have loved reading.”

“So, I’ve written too much now already, forgetting that “brevity is the soul of wit.” On the other hand, “I cried when I wrote this song; sue me if I play too long.”

“I’ll wind it up with just one more quotation. “It is with a heavy heart that I take up my pen to write these the last words in which I shall ever record the singular gifts by which my …” father, Hal Singleman, “was distinguished.” You are the one whom I will “…ever regard as the best and wisest man I have ever known.”

“I miss you.

Love,

Horace”