Today, February 16, 2023 (you’ll hear this a few weeks after I wrote it… I’m always ahead of schedule) is the 36th anniversary of the first time I stepped into my own classroom. I didn’t have a computer. Neither did anyone else I knew. I wrote my lesson plans by hand, and I followed strict guidelines for creating them. Goal, objective, procedure, and assessment were the elements I was expected to have. That’s what they taught me in my education classes. That was what my principal expected of me. But she expected something more.

I was trying to teach using the basal reader, “Ride the Sunrise.” It was fine, if entirely uninspiring. We would read the story together in class, and then the students would answer the questions and do the vocabulary exercises. It was hardly revolutionary teaching. It was, in fact, frighteningly dull.

My third week in, it was a Thursday after school, my principal called me into her office, and she asked me what the hell I was doing. I explained I was doing what I thought was expected of me. This was the district adopted textbook, and I was following it religiously.

She rolled her eyes. “I have a fleet of teachers who can do that. That wasn’t why I hired you. You told me you loved literature. You sat in that interview, and you talked about how much you loved Hemingway, Doyle, and Shakespeare.”

“Yes, ma’am, I did.”

“So why don’t I see those in your classroom? I’m sorry, Fred, but I’m really disappointed in you. I expected so much more.”

“You’re saying… let me understand you… you’re saying I should teach those things?”

“You got it. You talk a good game, but it doesn’t mean a thing if you can’t back it up.” I heard Ella Fitzgerald in my head: “It don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing.”

“The district has all those on reading lists for later grades. I’m teaching a 5/4 combination.” (That always made me think of Dave Brubeck.)

“So, let’s get your kids ahead of the game. Can you do that or not?”

“Oh… I think I can do that. Come see on Monday.”

I spent the weekend poring over “A Scandal In Bohemia.” I got more than a little stoned Saturday afternoon and watched the Jeremy Brett video with my notebook in my lap and a pen in my left hand, scribbling furiously. It’s not a mystery as much as it is a love story about a man who is incapable of love. How could I get my students to feel that? What could I ask? How could I get them to understand something that was at least 2 years over their reading level? I needed help. I called the greatest teacher I had ever known: my father.

“Do you understand Sherlock Holmes?” he asked.

“Obviously.”

“Excellent. Then explain it to them. You take it a piece at a time, just like I did when we read Curious George on the steps of the library. Read. Stop. Question. Rinse. Repeat. You get them through it a piece at a time, and you ask them about the things you think are interesting. Look at that opening line. ‘To Sherlock Holmes, she was always the woman.’ Read it to them. Stop. What on Earth does Watson mean by that? They’re old enough to have some ideas. Encourage those ideas. It’s playing, Fred. That’s all. You’re just playing.”

And that, gentle readers and listeners, is the key to learning. We learn by playing.

Play is often talked about as if it were a relief from serious learning. But for children play is serious learning. Play is really the work of childhood.

–Fred Rogers

But the sharp break that unfortunately prevails between the kindergarten and the grades is evidence that the theoretical distinction has practical implications. Under the title of play, the former is rendered unduly symbolic, fanciful, sentimental, and arbitrary; while under the antithetical caption of work the latter contains many tasks externally assigned. The former has no end and the latter an end so remote that only the educator, not the child, is aware that it is an end.

— John Dewey How We Think: Chapter 12: Activity and the Training of Thought

We gain experience through Play. Experience is The Great Teacher. It’s the interpretation of that experience that leads to real education. Education is not to be mistaken for memorization. It occurs only when we have experiences that open us up for other, greater experiences. It comes from finding the meanings of our experiences.

I got to school in practically the middle of the night Monday morning. I had to copy the story out of one of my paperbacks. I had to collate and staple together 35 copies. That was incredibly time consuming in 1987. When Mrs. Dobbs came to see my show on Monday morning, she was duly impressed, and she told me I was now on the right road. I followed it proudly.

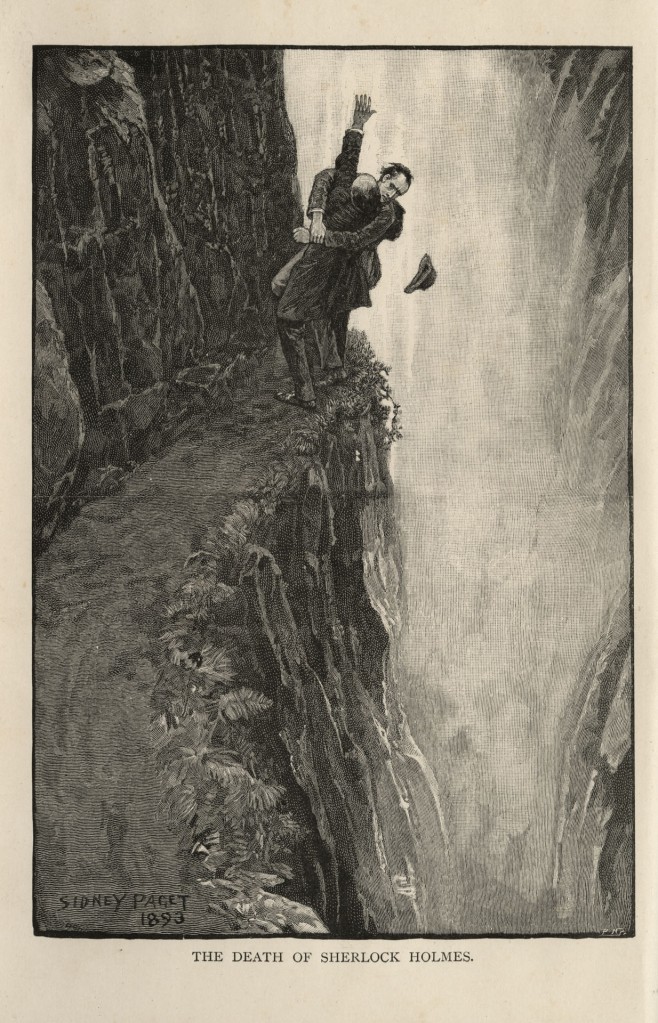

Within a few weeks, my students were easily spotted in the lunch room because they were the ones carrying around the Sherlock Holmes books they had made their parents buy them. Just before Christmas Break we read “The Final Problem,” in which Holmes dies… or at least we think he did. If this is a spoiler for you, I can’t bring myself to apologize. It’s 130 years old. You’ve had a minute to read it.

There was robust discussion, sometimes becoming far too animated for a normal classroom, about whether Holmes was really dead. Holmes and his archenemy, Professor Moriarty, had finally had the contest they were fated to have. Two sets of footprints go down to the edge of Reichenbach Falls. None return.

An examination by experts leaves little doubt that a personal contest between the two men ended, as it could hardly fail to end in such a situation, in their reeling over, locked in each other’s arms. Any attempt at recovering the bodies was absolutely hopeless, and there, deep down in that dreadful caldron of swirling water and seething foam, will lie for all time the most dangerous criminal and the foremost champion of the law of their generation.

— Sir Arthur Conan Doyle “The Final Problem”

Students were throwing theories back and forth like hand grenades, and they were exploded promptly by their classmates who told them why that idea was wrong, but their own ideas must certainly be right. And I sent them home to wonder for the next few weeks.

And you know what they did all by themselves during the break? Yes, that’s right. They ran to the bookstore and the public library to find “The Empty House,” which I told them was Watson’s own adventure. And without their teacher to hold their little hands… they read it… all by themselves. Okay… they didn’t all understand it as well as I wanted them to, but by the time we read it in class, and we watched the Jeremy Brett video, everyone had become a lifelong Sherlock Holmes fan.

There are worse things a teacher can do.

We performed Hamlet a couple of years later. I was constantly upping my game. By this time, we were doing Sherlock Holmes the first half of the year. Shakespeare occupied the second half. This particular year I had a child show up in my class who had spent her life in the back woods of Alabama. She had never seen a book. She didn’t know what the alphabet was. But I was teaching 6th grade that year, and Jenny was 12 years old. They put her in my class.

Her special ed teacher, Jody Novack, and I worked our asses off with Jenny. She was a very sweet girl who really wanted to learn. They made me give her the standardized test that year. I think it was called the CBEST, but don’t quote me on that. It was more than 30 years ago, and I can’t always remember what I had for lunch yesterday anymore so I could be wrong.

I asked if she could be exempted from taking the test since there was no way she could pass it. You might as well have given me a test in Japanese. She was just up to the level of Dr. Seuss by the time the test was to be administered. No, the district told me, she had to take the test. Could I at least read it to her so there might be some means of this revealing what Jenny knew? No. That’s not allowed. Fine.

When I gave her the test, Jenny asked what she was supposed to do. I told her to fill in one bubble on each line. She was happy to do that. She made a pretty little pattern down the page.

When she finished, she pulled out the Hamlet script we were doing and went one word at a time as Mrs. Novack had taught her to do. She was determined to learn to read that because she desperately wanted to play Ophelia. “Read one word, Jenny. Then read the next one, and put the two words together. Then do the third word. Keep doing that until you have the whole sentence. Then read the sentence and know you did it.” Mrs. Novack’s method was time consuming but effective.

I mention this test only because when we got the results back, Jenny was in the 35th percentile. Standardized tests measure nothing meaningful. If you want a meaningful measurement, you should have watched Jenny raving like a lunatic after Ophelia’s brother, Laertes, and her father, Polonius, are killed by her boyfriend, Hamlet. To this day, I can hear Jenny on that stage…

There’s rosemary, that’s for remembrance. Pray you, love, remember. And there is pansies, that’s for thoughts. . . . There’s fennel for you, and columbines. There’s rue for you, and here’s some for me; we may call it herb of grace o’Sundays. You must wear your rue with a difference. There’s a daisy. I would give you some violets, but they withered all when my father died. They say he made a good end.

All right, she wasn’t Kate Winslet, but when she took her curtain call, all 40 people in the audience gave her a standing ovation. And I never saw anyone glowing with more pride. That’s how you measure student success.

Six years later, she was graduating from high school, and she called our school and told my principal that she, Jody Novack, and I all had to come to her graduation because she was making a speech. We took the morning off and went to see Jenny in her robes on the stage.

“When I got here to California, I didn’t know how to read. It was easy to think I was dumb, but I had a couple of teachers and a principal who refused to believe that. Mrs. Novack worked with me every day before and after school on my lines for Hamlet because Mr. Eder let me play Ophelia. Mr. Eder was completely convinced I could do it, and he convinced me. Today you can ask me anything you want about Hamlet, and I can give you an intelligent answer. Because they were right. I wasn’t dumb. I just needed a little help.” And then Jenny looked over to me, and she said words I’ve never forgotten. “To be or not to be, Mr. Eder? I choose to be.”

I cried like a little girl. More than 30 years later, I get tears in my eyes every time I think of that moment.

That’s why we teach. That’s why I taught.

And then it began to crumble. It began with No Child Left Behind, but that was certainly not the end of it. Someone realized that a state might spend as much as 20% of its budget on public education. There was money to be made there. The testing industry promptly produced tests that showed that public education was failing, that our students were stupid, and that only by using the curriculum designed by the testing companies could we possibly save our students. It was Professor Harold Hill’s Boys’ Band coming to rescue us from the evils of the Pool Hall.

Imagination was banned from my classroom by the time I quit in 2016. There would be no more school plays. There would be no more Sherlock Holmes, no more Shakespeare, and I was dreaming if I thought I could teach To Kill a Mockingbird to a 6th grader. It was about data. How many words per minute can they read? Why this matters is a complete mystery to me. I don’t know many people who love reading who are in a hurry to zip through the book. If I take you out to a 5-Star restaurant, are you really going to see how quickly you can consume the steak, or are you going to savor every morsel? If you’re reading this, I hope you’re taking the time to enjoy it. If you’re listening to it, I promise I’m not rushing. I would like you to be able to absorb each word. Since some people have difficulty with that because of my use of music, I always include the transcript so you can follow along at a good pace.

Public education has been bought and destroyed by corporations. I have great respect for those who continue to try, but if I can’t help Jenny anymore, if I can’t watch my students’ eyes light up as they begin to understand what people have told them they couldn’t even read, I don’t want any part of it. I’ll leave you with words no corporation could ever understand.

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. . . . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

— Percy Bysshe Shelley